Introduction

According to its dictionary explanation, an estimate is a guess of what the size, weight, value, amount, cost, duration of something might be.

It goes without saying that a prediction of what will happen in the future is something that can't be accurate and fixed by definition.

Nevertheless we are often asked to provide the "right estimate" for a software project in a short period of time (because bids don't wait) and, to make things worse, without a clear understanding of the context.

Why estimates don't work

Before presenting my approach to calculating a project cost, I'd like to recap the two key factors that undermine estimates accuracy:

- Accidental complication

- Unknown unknowns

Accidental complication

In his famous video "7 Minutes, 26 Seconds, and the Fundamental Theorem of Agile Software Development", J. B. Rainsberger shows how the total cost of a feature can be expressed as the sum of the cost of essential complication with the cost of accidental complication.

Essential complication is due to the fact that the problem we have to solve is hard. But, as domain experts, we can exploit our skills, discover similarities and be good enough at estimating the cost of essential complication.

Accidental complication is due to the fact that we are not so good at our jobs. It's the errors we make at designing systems; it's the mess we leave in our code because we have no time to clean it up; it's the overhead we introduce when we add people to a project (thinking that nine women can make a baby in one month).

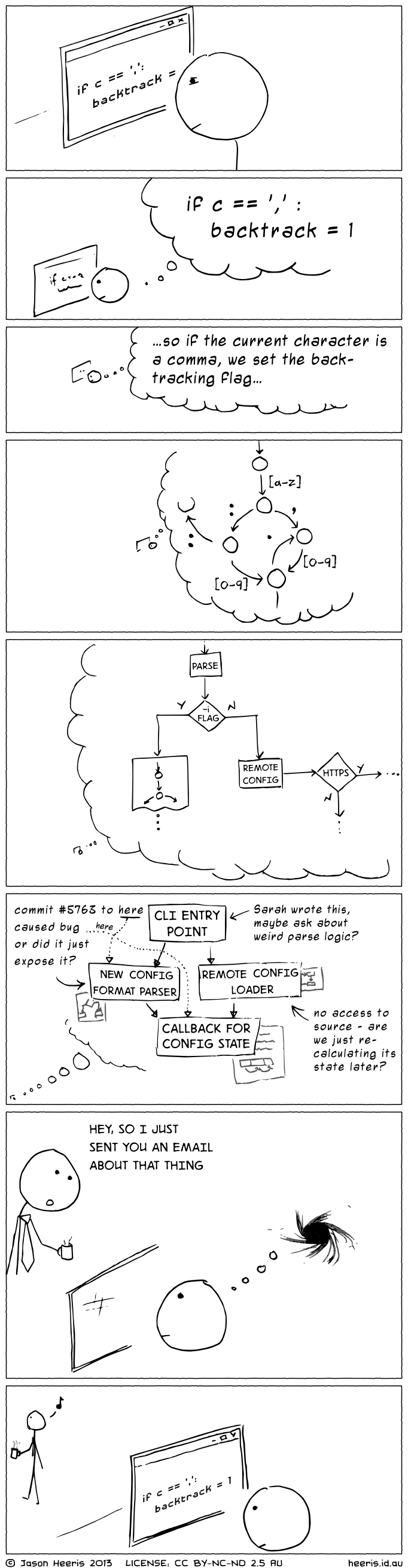

As we can guess, the list is a long one and the following comic strip by Jason Heeris is just another hilarious but meaningful example of accidental complication:

Since the cost of accidental complication dominates the one of essential complication, one way to make the total cost more predictable is reducing accidental complication as much as we can.

Unknown unknowns

Another aspect that has a very big impact on estimates accuracy is our attitude to ignore events that are outside the model under investigation.

Indeed it's easier to focus only on the known unknowns, that are things that we know we don't know.

For example, if a requirement is "I want marketing automation" we don't know what exact features the customer needs but, since we know what's unknown, we can make some analysis on that domain to provide a better estimate of the cost.

Here is another, not so highly improbable, example of unknown unknown: a platform security patch released in the middle of the project development which breaks, say, our brand new integration with the marketing automation system. Sounds familiar, doesn't it?

We can't predict such an event because it isn't under our control. What's more, we can't avoid applying the patch, since it solves a security issue that has just become public and exposes the customer to potential risks.

Sure enough, the patch release has nothing to do with the domain we were focused on and every minute spent dealing with it isn't included in our estimate.

We can fill out a detailed list of highly improbable events that can occur, the so called black swans that change the game and send our estimates up in smoke.

But we can't rely on such list because, like it or not, uncertainty will always find it's way into the project in new, fancy and unpredictable ways.

Calculating a project cost

As we have seen so far, to calculate a project cost we can't take into account only essential complication but also accidental complication and uncertainty.

Thus, to estimate the cost of a project development, we can apply the following rules:

- Reach consensus on essential complication

- Do our best to reduce accidental complication

- Prepare for change

Reach consensus on essential complication

We know how to estimate essential complication: we can count on our attitude to find similarities and weight features based on our past experience.

Write down all the features; we can choose the formalism we prefer but let's consider writing them down as user stories. The main benefit of user stories, to me, is their focus on purpose, that is the reason why a feature is needed.

Then gather the team that will be responsible of bringing those requirements to life. I use the general term team and not developers because a feature is not necessarily a matter of pure software development. Ideally even the customer should take part to this activity, mainly to provide more details during discussion.

Ask the team to estimate the effort of development of each feature.

To express the effort we can use man-hours, man-days, story points, bananas or another unit we like.

Whatever the unit, I warmly suggest to use a non-linear sequence like: 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 20, 40, 100.

This way the higher the estimate the more the people will be obliged to make a choice between distant numbers, unleashing uncertainty and generating more discussion and details.

This, in turn, will likely bring to break the requirement into smaller and more estimable chunks.

For each requirement:

- each team member writes down his or her own estimate without sharing it with others until the next step;

- all members' estimates are revealed and compared one by one; differences generate discussion that goes on until the team reaches the consensus on a number;

- if consensus isn't reached in a reasonable amount of time (minutes) it likely means that some information is missing; ask more details to the customer, if possible, and estimate again; alternatively trust the estimate from the ones who have some past experience on the development of a similar requirement.

This technique is called planning poker and it definitely makes the estimating process more fun. And if estimating is fun, people will be willing to do it.

It takes a while to get used to this technique but after the initial inertia it's impressive how fast it turns out.

I've used this technique a lot (both using printed cards or this free tool) and the real benefit it gives is the discussion and the seek for details that it generates.

Do our best to reduce accidental complication

Dealing with the root causes that produce accidental complication is a good way to reduce it.

For example, performing code refactoring is a good way to "clean the kitchen" and wipe out technical debt, that is, accidental complication.

Writing automated tests is a proven way to encourage refactoring.

Test driven development (TDD) lets us design better systems, because it avoids premature optimizations and over-engineering.

Pair programming and code review are other techniques that can help us catching design defects earlier.

Useless to say, learning and using solid programming principles and the best available tools and habits is gold.

Since there aren't work-for-all recipes, my advice is that of trying them and choosing those that give us concrete benefits.

To accomplish this goal it's important to measure the outcome: write down the time we spend developing features, use different techniques to develop the same (or equal-weighted ones) and compare the result. Measuring is the key.

Note: before the planning poker session begins we should be clear with the team: the additional cost of applying practices that reduce accidental complication should be taken into consideration.

Prepare for change

If we accept the idea that, sooner or later, uncertainty will mess up things within the project, we need to be prepared for change.

Since unknown unknowns can impact both project costs and delivery dates, embracing change means giving up the illusion that we can control every aspect of the project through a long-term plan (usually represented with a Gantt chart).

Just like a sat nav system does when it drives us from A to B, we need to be ready to recalculate our route as soon as an unexpected event occurs and changes the plan.

This likely means that project costs increase or delivery dates change, so our customer should be prepared. Obviously nobody is happy if this happens but after all we are not paid solely to work for a fixed amount of time or money, we are hired to reach a goal. If something obstacles us, the best we can do is finding alternatives to reach that goal; stopping in the middle of a project not to exceed a fixed time or budget doesn't bring any value to the customer.

Let's consider that exceeding time or budget is not always mandatory: we can reduce the scope and make our best to respect time and budget constraints.

To be able to reduce the scope it's essential to prioritize tasks and define what can be postponed or dropped out when we will encounter black swans.

Conclusion

As we have seen, calculating a project cost is not only a matter of estimating how difficult it is to develop a set of features.

There are other factors that have a huge impact and that have to be taken into consideration in order to give a prediction that is as close as possible to reality.

Nevertheless, we can't avoid to be prepared to embrace change, because thinking that everything can be under control is an illusion.

If you have your opinion about some of the tools and techniques I mentioned in this article or have different experiences you like to share, please leave a comment or contact me and let's discuss about that.

Bibliography

- Duarte, Vasco. No Estimates: How to measure project progress without estimating. OikosofySeries, 2016. Web. http://noestimatesbook.com/.

- Rainsberger, J. B. 7 Minutes, 26 Seconds, and the Fundamental Theorem of Agile Software Development. Web. https://vimeo.com/79106557

- Brooks, Frederick P. The Mythical Man-month: Essays on Software Engineering. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Pub., 1982. Print.

- Fowler, Martin, and Kent Beck. Refactoring: Improving the Design of Existing Code. Boston: Addison-Wesley, 2000. Print.

- Taleb, Nassim Nicholas. The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable. New York: Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2010. Print.

- Taleb, Nassim Nicholas. Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder. New York: Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2014. Print.